January 2, 2024

There’s an old Japanese proverb that says, “the bamboo that bends is stronger than the oak that resists.” That may well describe today’s “bend but do not break” economy.

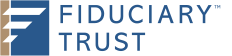

On the face of it, 2023 was a most improbable year. Several material events failed to land much of an economic or market impact, including two land wars; a banking crisis that brought down several large banks and forced a central bank backstop of the entire banking system; a budget-induced legislative deadlock that resulted in another round of U.S. sovereign debt downgrades; and a prolonged and deeply inverted yield curve. Through it all, the economy swayed but did not break. Markets appeared to brush it off. The landscape of returns for 2023 makes the point. (Exhibit A)

Exhibit A: Total Returns by Asset Class

It is hard to recall another time when a banking crisis, inverted yield curve, and the inevitable slowing of credit creation did not result in some sort of economic dislocation.

Despite this catalog of woe, the economy remains in remarkably fine fettle. Real gross domestic product grew at an annual rate of 5.2% in the third quarter, its fastest pace since the fourth quarter of 2021, when pent-up demand from the pandemic was unleashed as the economy reopened.1 While the economy slowed in the fourth quarter,2 it remains surprisingly resilient thanks to the ongoing strength of the labor market.

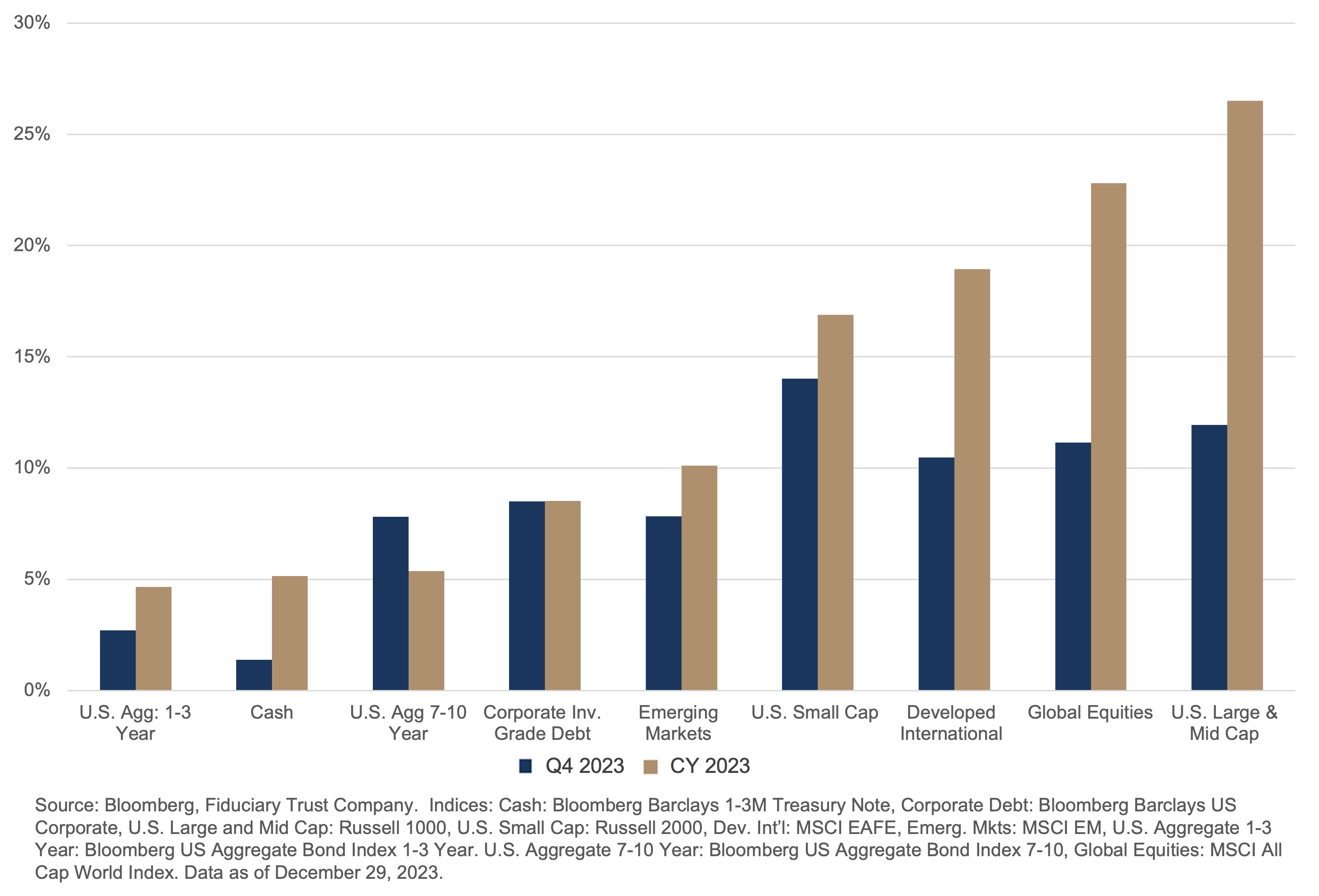

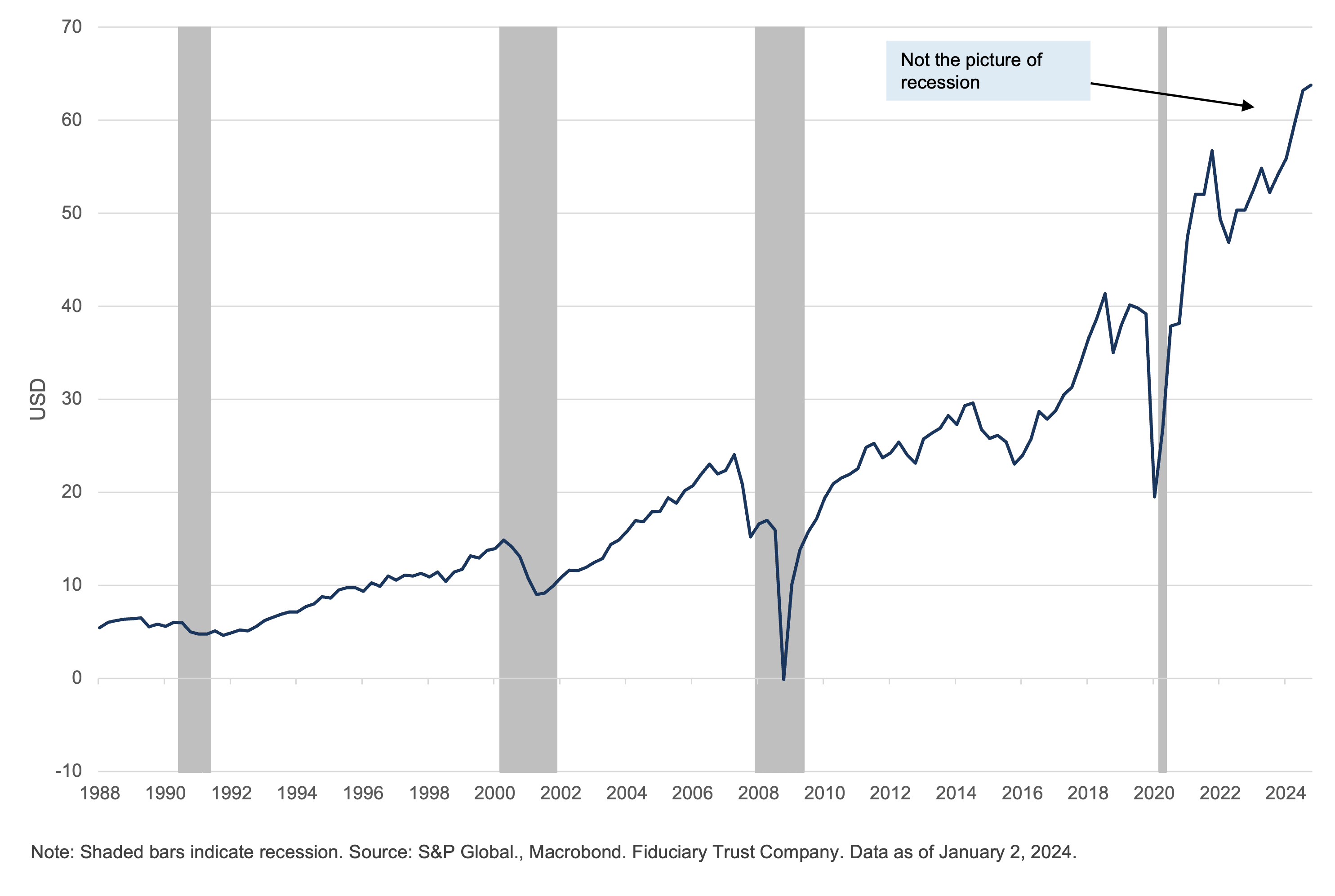

In the face of high interest rates, tightening bank lending standards, waning homebuilder confidence, and 15 consecutive months of below-average small business confidence, the economy managed to produce nearly 200,000 jobs in November.3 This brings the total for the 11 months to more than 2.5 million. The unemployment rate now stands at an impressive 3.7%.4 As we’ve pointed out in the past, until there is a material increase in job losses, it’s hard to think a recession is a lurking threat. This perspective is reinforced by the NBER Recession Criteria, which show generally improving conditions on multiple fronts. (Exhibit B)

Exhibit B: NBER Recession Criteria

In fact, fewer than one-third of forecasters polled by Bloomberg are bracing for a recession.5 To be sure, economists have a track record largely unburdened by success. A 2023 recession failed to materialize, despite being so broadly predicted that it was practically scheduled. Remarkably the stock market failed to register much concern, only managing to produce an impressively short and mild correction in October. If one looked away, it was missed. In many ways, 2023 was the year of no landing.

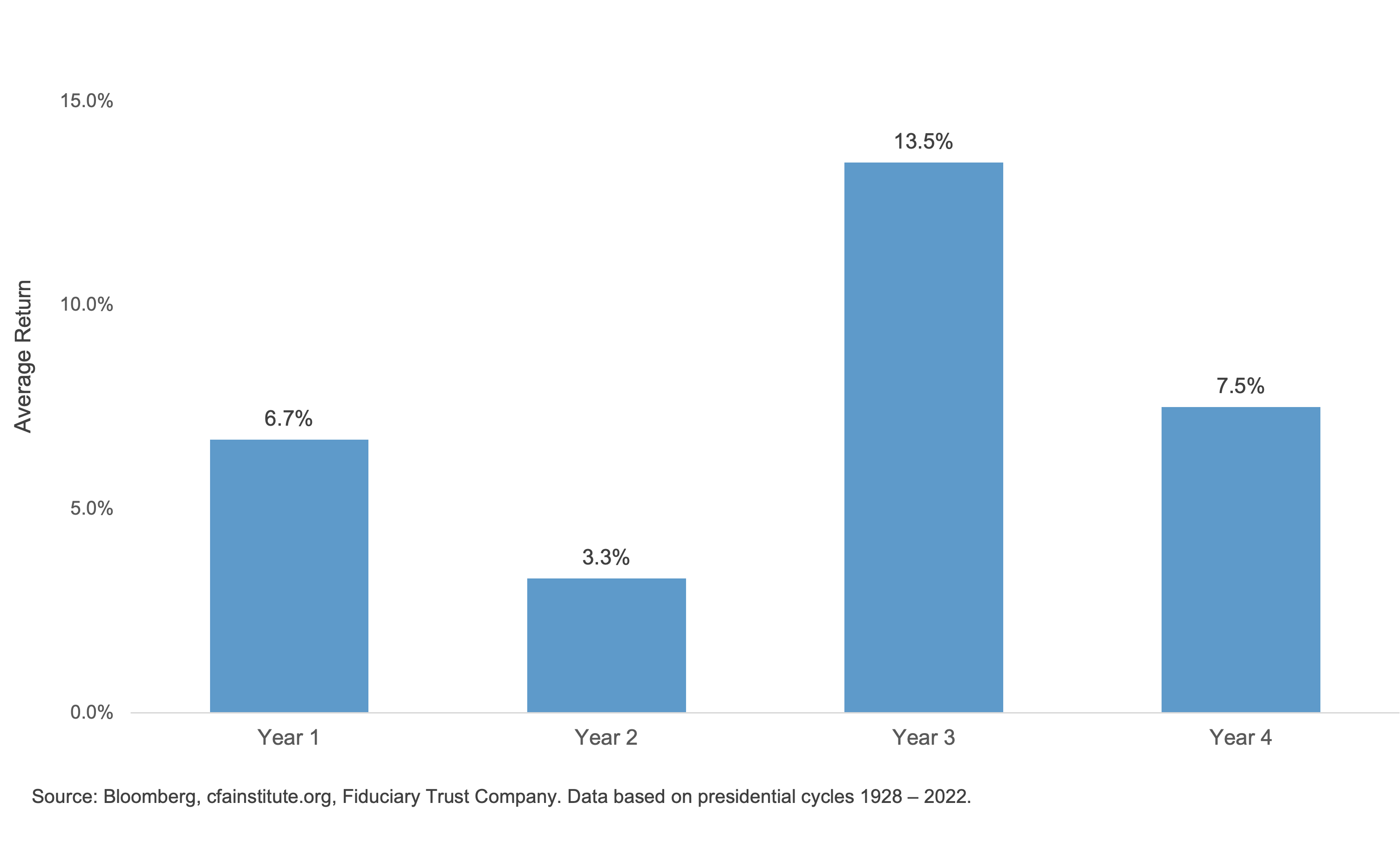

If past is prologue, 2024 is likely to be a good year for both the economy and markets, as recessions rarely coincide with presidential elections. In fact, election years have historically been the second-best year for stocks in a presidential cycle. This isn’t terribly surprising, as those in power are motivated to delay the onset of recessions until after the vote, and this includes not just elected officials but the Federal Reserve chairs who are appointed by the winners.

This isn’t to say that a recession couldn’t happen in 2024. Recession has occurred in six of 24 presidential election years. However, three of those six occurred during extraordinary periods: the Great Depression, the Great Financial Crisis, and the pandemic. However, policy-induced recessions are exceedingly rare during an election year.

The Arch of Probability in 2024

Soft Landing into a Goldilocks Economy

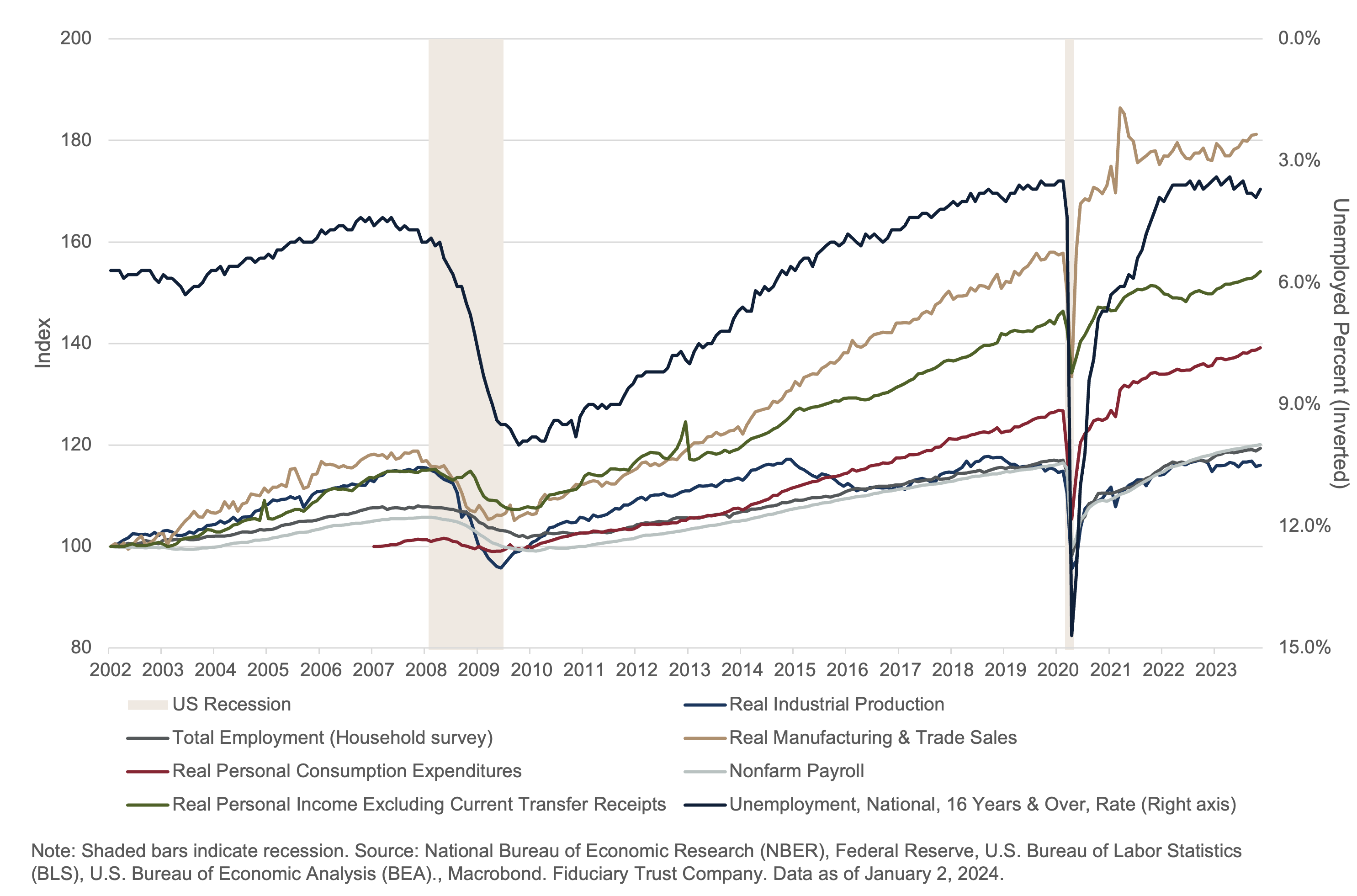

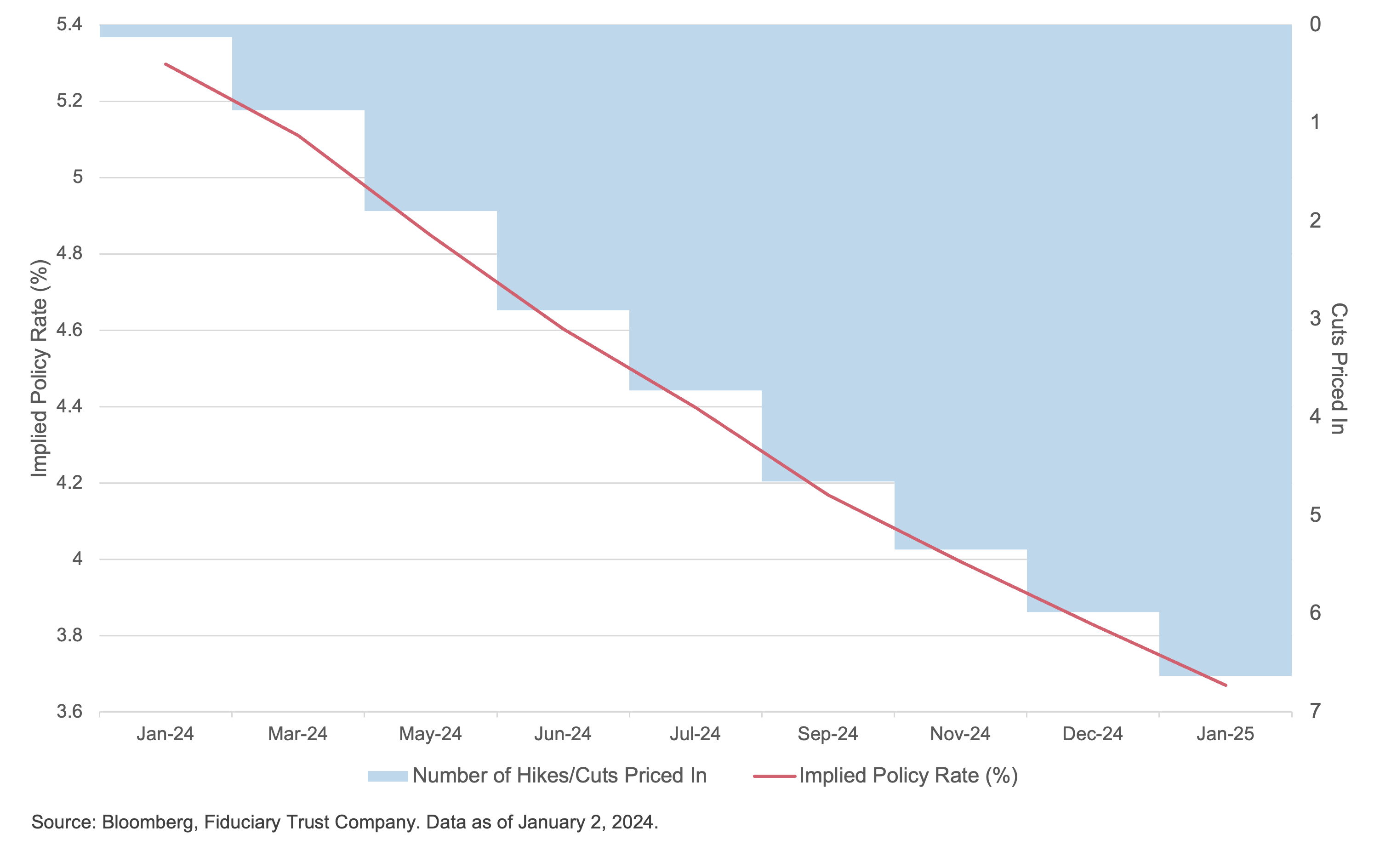

This brings us to an interesting thought experiment: dimensioning the landscape that investors will face in 2024. Constructing an array of possibilities along a continuum is a useful way to conceptualize the landscape. In other words, we can build a stylized probability distribution curve where multiple futures can be assessed. (Exhibit C) The broad consensus holds that a soft landing will unfold when the economy slows enough, allowing inflation to cool down and facilitate a series of interest rate cuts. This view believes that the economy can slide into a lower gear without a recession. Federal Funds futures predicts almost six rate cuts, totaling roughly 150 basis points6. (Exhibit D)

Exhibit C: A Stylized Landscape of Growth Scenarios in 2024

Exhibit D: Expected Path of Federal Funds Rate

Economic growth is estimated to be 1.2% in 2024 according to Bloomberg. The Federal Reserve’s forecast is somewhere between 1.2% and 1.7%.7 Earnings for the S&P 500 are expected to rise 11.5% on 5.5% revenue growth8. (Exhibit E) This soft landing is a Goldilocks scenario, representing the best of all worlds and playing to expectations that, all things being equal, means fewer market ructions for investors.

Exhibit E: S&P 500 Quarterly Operating Earnings

No Landing

But what if this bamboo-like economy turns out to be even more resilient than that? What if instead of a gentle touch down, there is no landing but continued growth as employment remains strong and growth higher than expected? Over the past year or so, investors would have dismissed this notion as wishful thinking or folly.9 Indeed, it was dismissed last year. Yet given the forecasting acumen of the profession, it’s a possibility worth considering. This scenario represents moving into the tail of probabilities and surprises not priced.

The idea of no landing is easier to consider in the sterile conditions of a thought experiment than in the messiness of reality. The expectation of lower interest rates that have yet to be realized by the central bank have propelled asset prices broadly higher during the closing months of 2023. The calculus of a no-landing scenario will upset the expectations of investors and the plans of policymakers, as higher growth forces more pressure on prices and prevents anticipated interest rate cuts. Under a no-landing scenario, the collision of lower rate expectations with the reality of higher rates for longer will predictably be the source of impressive market volatility.

Whatever 2024 brings, central bankers will likely keep interest rates high enough to prevent another bout of inflation. From our perch, this means that Powell & Co. will fail to cut interest rates in line with the market’s current expectations. Indeed, after the December Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the dot plot illustrating each central banker’s forecasted for Federal Funds rates going forward showed only three cuts forecast for 2024, relative to the six cuts expected by the markets, as outlined above.10

Some of this reluctance to play to the market’s script may be attributable to the ghost of Arthur F. Burns, the last Fed chairman to lose control of inflation, resulting in America’s last real bout of it, which turned into stagflation during the 1970s and early 1980s.

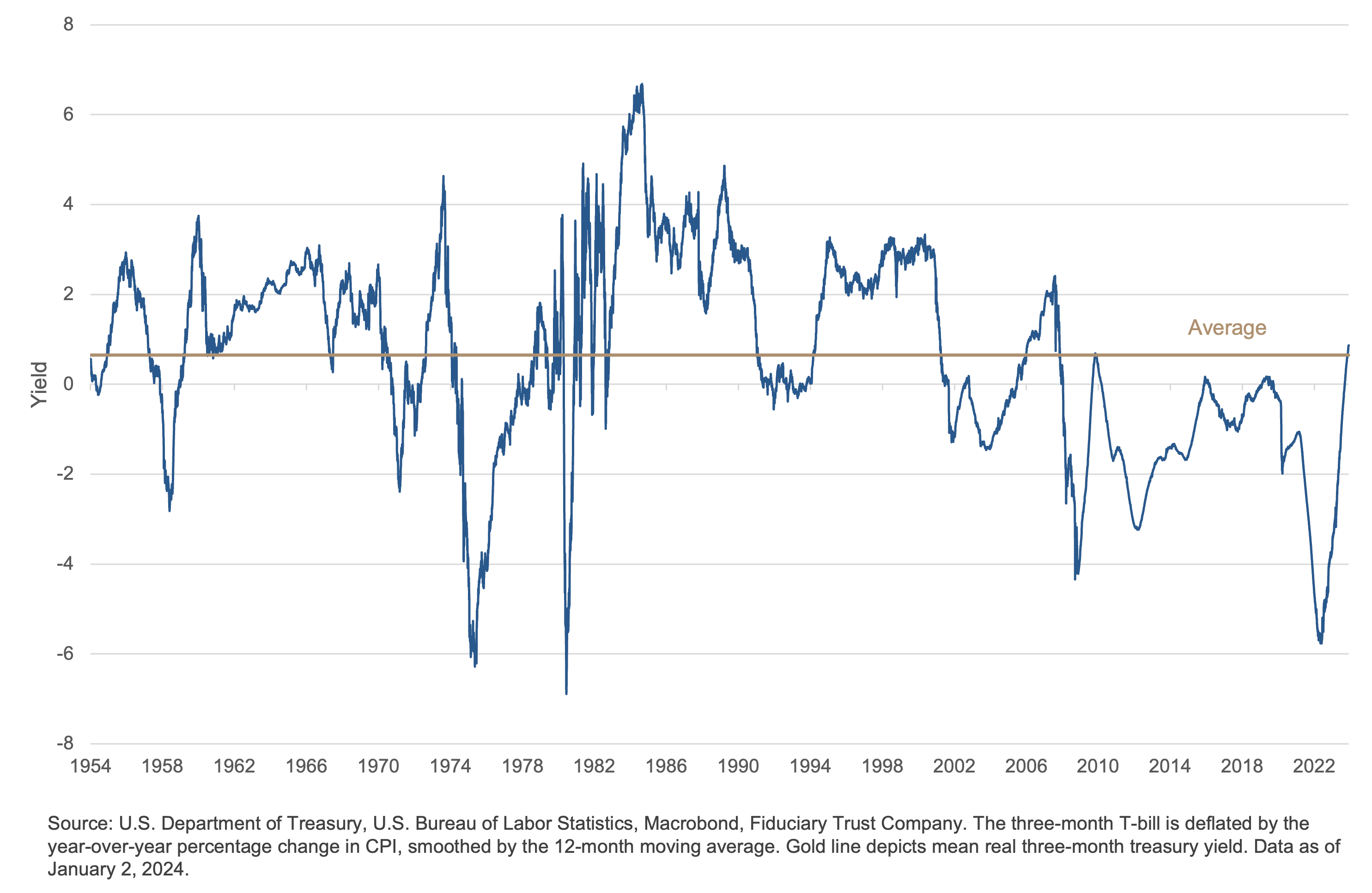

By most accounts, inflation has steadily moderated over the past year and a half. The overall rate of inflation, for instance, fell to 3.1% in November, down from 9.1% in June 2022.11 At the same time, real three-month Treasury yields have finally reverted to their historic levels. Since 1955, the spread between three-month T-bills and the year-over-year percentage change in the Consumer Price Index averaged roughly 65 basis points. Since the Fed slashed short-term rates in the global financial crisis, however, real three-month yields have been materially and durably negative. Recently, they bounced back to 62 basis points, suggesting the price of money has finally returned to its normalized relationship with the price of things. (Exhibit F) This return to normal shows no significant threat to employment or growth. The idea that positive real interest rates would not be accompanied by damaged employment and economic growth was unthinkable in recent times.

Exhibit F: Real Three-Month Treasury Yield

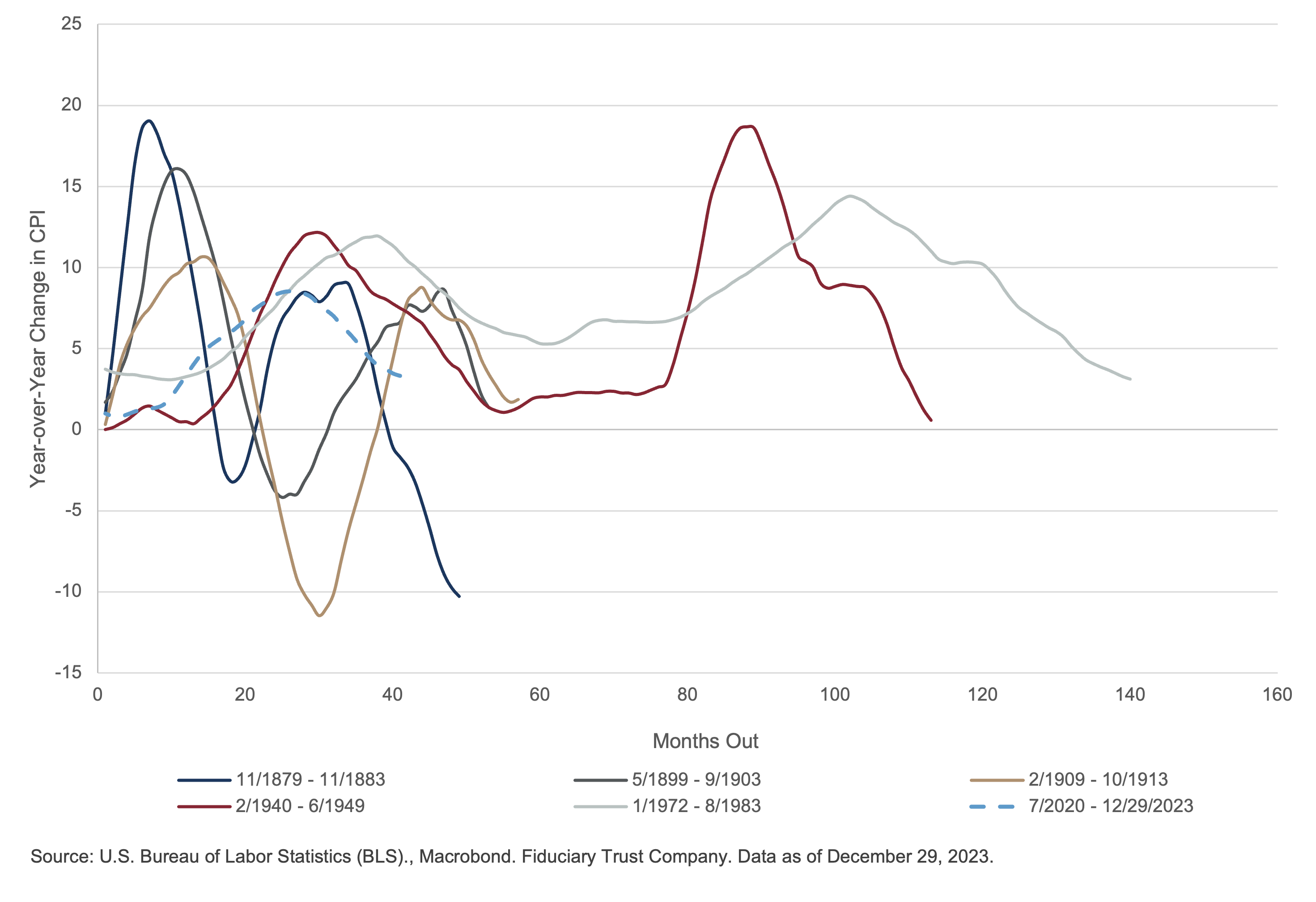

Though this suggests some sense of stability is at hand, significant flare-ups in inflation are rarely put down with one pass. If history is a guide, bouts of inflation tend to peak multiple times before policymakers can arrest it. Data stretching from the 1880s reveals that once inflation pushes through 10%, the secondary and tertiary impacts from the initial bout reverberate, causing second inflationary episodes. (Exhibit G)

Exhibit G: The Behavior of Prices During Periods of High Inflation

Portfolio Considerations

Equities

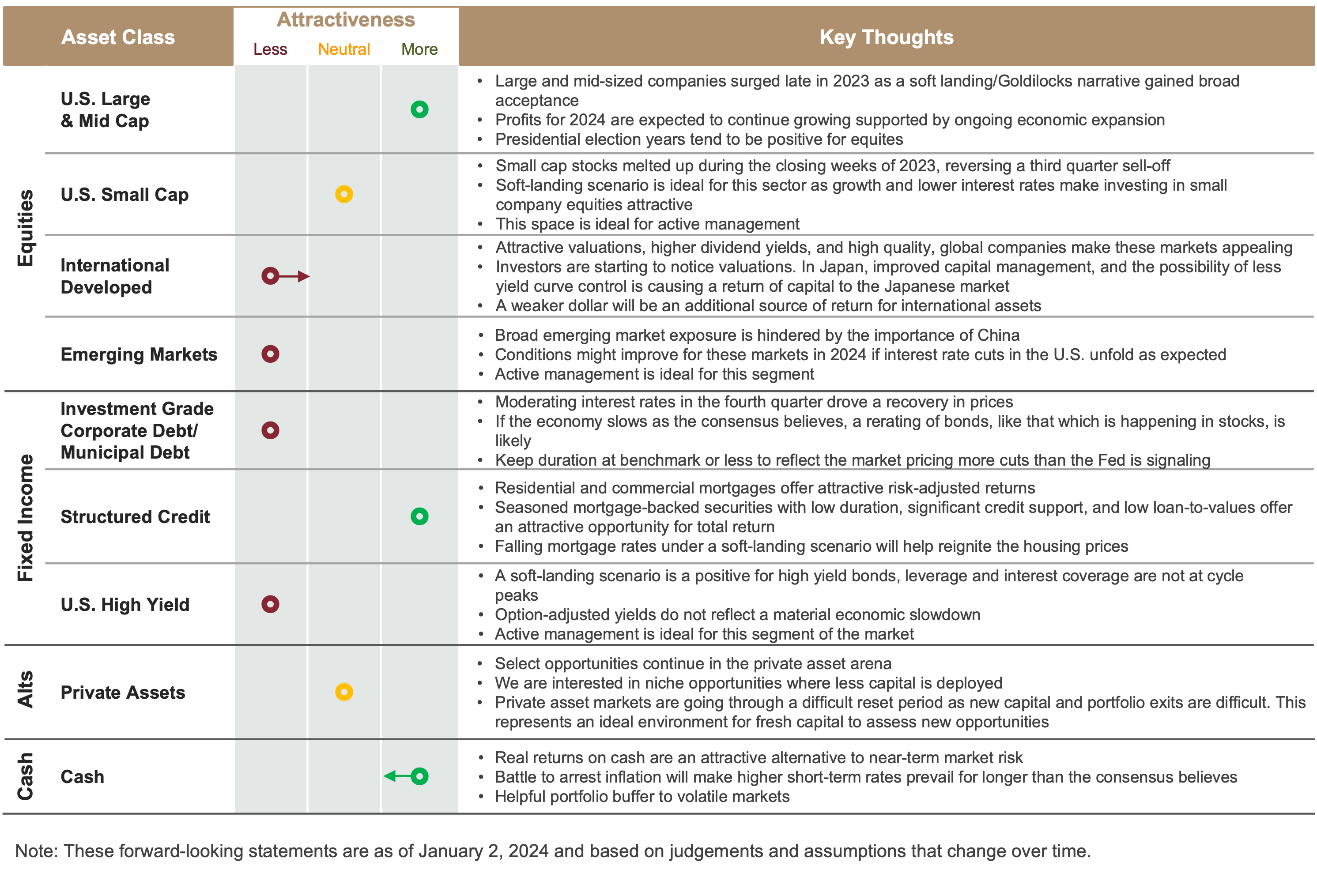

In a soft-landing or no-landing scenario, equities should show well. Secondary benefits might unfold as well. A strong public market might facilitate a reopening of the IPO market, which would be enthusiastically welcomed by the private equity market. U.S. equities will likely be the standout again this year if the interest rate story plays out as expected. However, international equities could surprise, as currency effects could figure prominently in returns. Japan might very well be the sleeper market again in 2024 as yield curve control relents and a real rate of interest emerges.

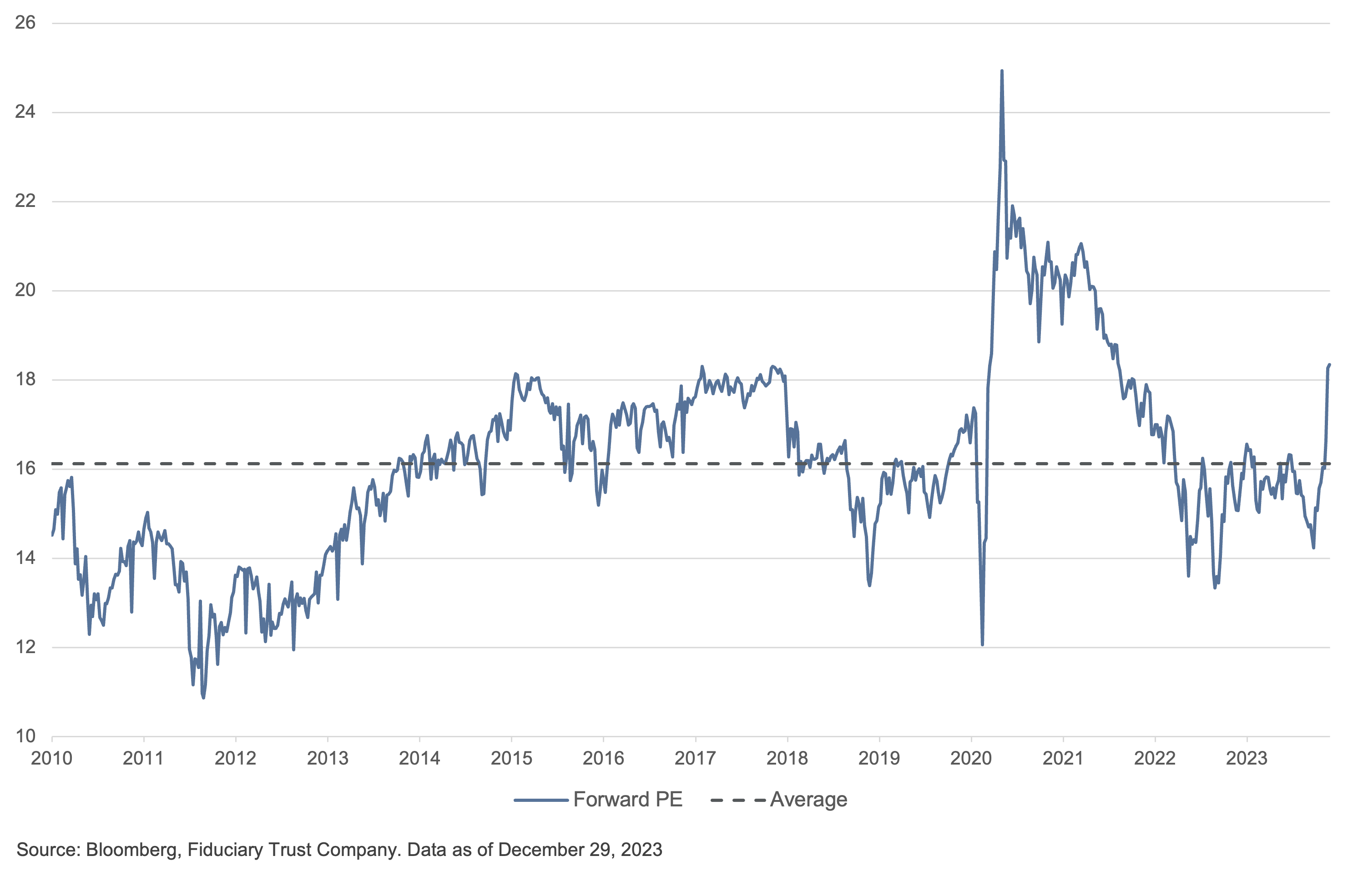

We are penciling returns for the American market in the 6%-10% range—7.5% is the average for a presidential election year. (Exhibit H) In a no-landing scenario, we might expect the average stock in the market to do somewhat better, as earnings could surprise. However, the volatility could be emetic, as the failure of rates to follow the script would force a reset in the bond market. Whether the Magnificent 7 will lead the way again in 2024 remains a question.12 The drivers of growth will likely remain under the soft landing, but company-specific challenges will likely force differentiation in performance for some of these stocks. Valuations for the average stock, as represented by the S&P 500 Equal Weight P/E, are close to the relatively undemanding longer-term averages. (Exhibit I)

Exhibit H: The Presidential Cycle and S&P 500 Returns

Exhibit I: S&P Equal Weight Forward Price/Earnings Ratio

Fixed Income

If, as expected, a recession is not a 2024 issue, bonds should do reasonably well. This would be particularly true if the market is headed toward a Goldilocks scenario with softening inflation, moderating employment growth, and rate cuts.

As previously noted, a no-landing scenario will cause a fundamental reset of interest rates, possibly pushing the 10-year treasury back to the 5% level. This will provide bruising losses for those investors who extended portfolio duration. Portfolio duration of roughly five years is justifiable, given the uncertainty of how things might play. Shorter duration but higher yield, whether through securitized credit or other forms of carry, should perform well if the soft-landing scenario plays out. If a no-landing scenario surprises, the yield will cushion any declines that duration causes.

International

While a recession may not be the likely scenario in the U.S. this year, it’s harder to make that case in Europe, where much of the continent and the United Kingdom have been flirting with contraction for some time. Remarkably, while the headlines have been reliably dour for Europe, returns across the continent have been comparable to the U.S. Markets in Spain, France, Germany, and Sweden posted gains of 34%, 22%, 24%, and 26% respectively in dollar terms. Betting on a repeat of 2023 in 2024 takes a leap of faith, but if interest rates in the bloc do not follow the U.S., then lower, dollar-based investors might find currency exposure a source of return.

In Asia, the Bank of Japan continues its program of loosening yield curve control. Japan appears finally headed back to real positive rates which has started a process of repatriating capital to that market, lifting the Nikkei 225 Index to levels not seen since 1990. In addition to the end of strict yield curve controls, investors are also finding improved capital management and attractive valuations. The return of capital has also strengthened the yen recently, which raises the question as to whether we’re in the peaking process of the dollar’s value.

Last year, we asserted that the dollar reached its peak in the third quarter of 2022. We reiterate this call as the interest rate cycle in the U.S. moves into its next phase. While the Federal Reserve is sending signals of rate cuts in 2024, the monetary mandarins at the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan are holding fast to higher rates, which will place pressure on the dollar. Consequently, currency exposure beyond the dollar will help boost returns across international assets. The dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency remains firmly in place, despite efforts by China and others to create alternative payment systems based on other currencies.

Into the New Year

The sum of all of this is a growing economy that drives rising profits against the backdrop of slowing inflation: an idyllic landscape for risk assets. Reflecting this state of play, we will reset the defensive portfolio posture we held last year by adding risk exposure to both domestic and international markets. It is important to note that, unlike 2023, where disruptive events failed to exert a meaningful and durable impact on asset prices, 2024 could bring a sharp break from this pattern. An election year with a volatile electorate, an economy that shows no immediate bowing to the business cycle, and markets that have priced moderating growth and inflation with a great deal of confidence is a recipe for surprise. Surprises against a backdrop of optimistic certainty will undoubtedly cause impressive volatility that will make the returns enjoyed feel hard won.

Exhibit J: Fiduciary Trust’s Asset Class Perspective

Below is a link to our Fiduciary Perspective, which includes a copy of the Market Outlook.