This year is off to a volatile start. The combination of a deeply inverted yield curve and a brewing bank panic that claimed a 167-year-old Swiss bank, a Silicon Valley stalwart, and a curious regional bank with deep ties to the crypto world have set investors’ teeth on edge. Meanwhile, central banks continue to raise interest rates. And as for the Federal Reserve, it continues to shrink its balance sheet. In short, financial conditions continue to tighten as the battle to arrest inflation continues.

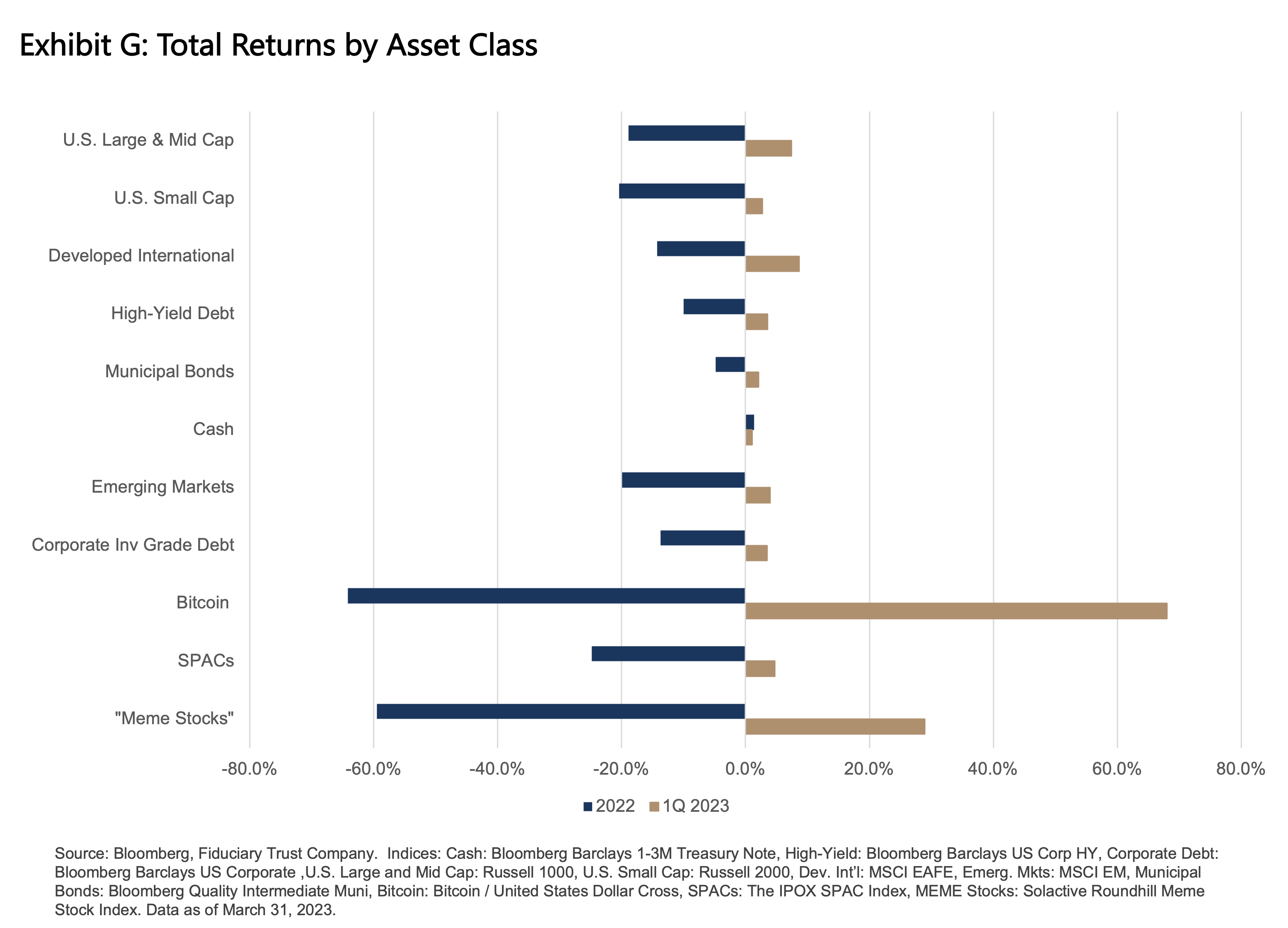

We have been Argus-eyed for what might break in this environment. Higher interest rates and falling money growth are a deadly combination to the “everything bubble” of recent years. While equity and bond markets suffered a tough go in 2022, it’s the recent spate of bank failures that landed the true body blow. We expected that the first casualty to emerge would be in the private asset space, specifically in venture capital. It turns out the banker to the venture capital community was the first to fall.

Banking is a unique business. Through the magic of fractional reserve banking, deposits create money. Consequently, banking is also a leveraged business: a slice of equity supporting enormous assets in the forms of investments and loans. Finally, banking is built on a foundation of trust and faith. Depositors, trusting that bankers handle their deposits judiciously through solid loans and investments, have faith in placing those deposits with the bank. When the former is in question, the latter is lost, and bank runs ensue. This is the essence of the story behind the failures of Credit Suisse and Silicon Valley Bank.

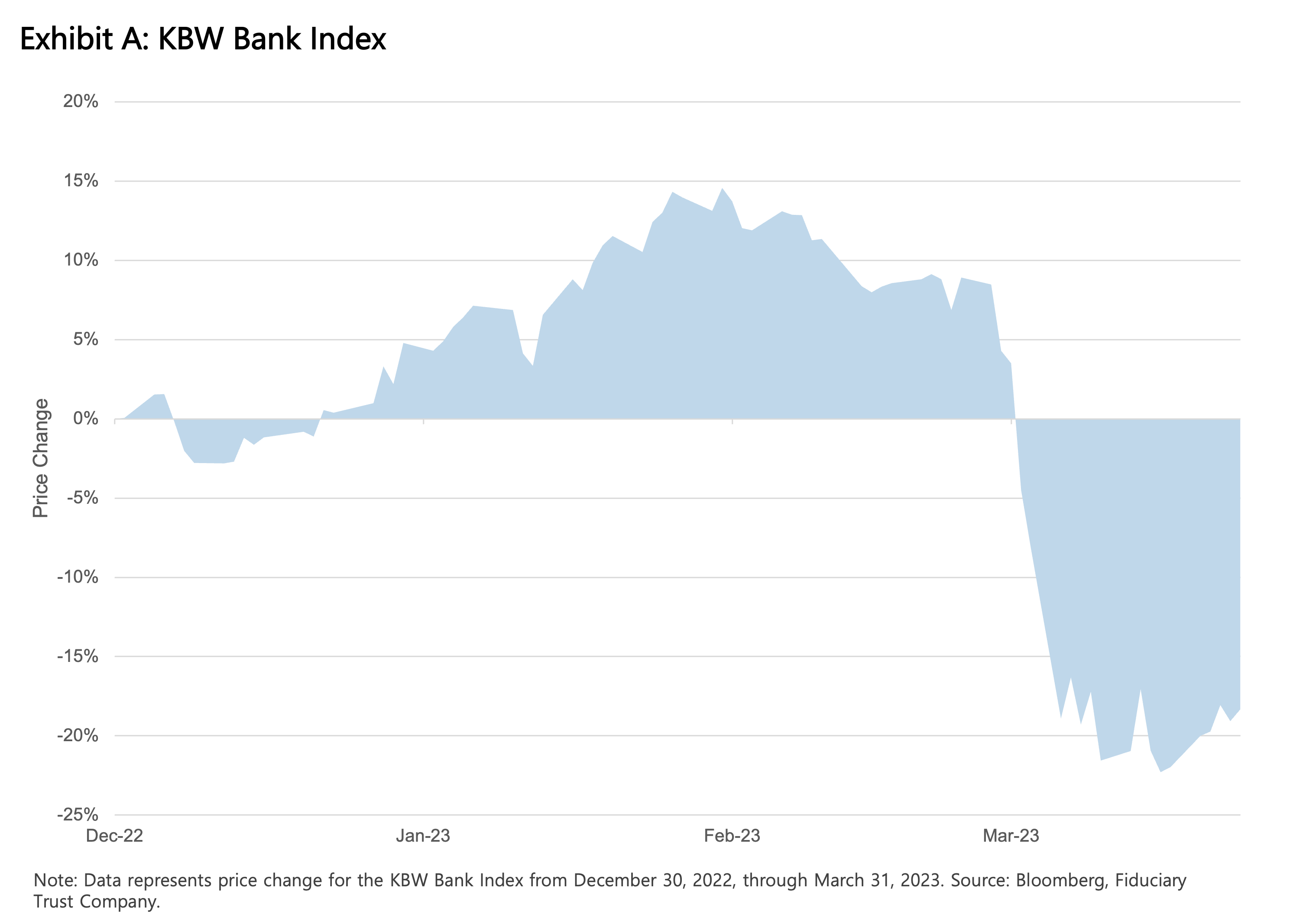

Bank runs create collateral damage as shaken investors feverishly cast about to identify the next problem bank. The resulting declines can be eye watering: The KBW Bank Index of 24 national money center and regional banks dropped more than 29% in 23 days.1 Predictably and thankfully, regulatory authorities stepped into the fray to backstop uninsured deposits and create lending facilities, adding liquidity to the banking system, all to buy time for a restoring of confidence. Judging from the recent price action of bank stocks, the scare seems to be subsiding.

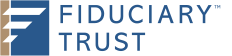

What all this portends for markets is not encouraging. Never, in our long dealings in markets, have we seen an economy beset by a prolonged, steeply inverted yield curve along with a banking scare that didn’t end in some sort of economic slowdown. Looking under the hood at how loans are made, rising interest rates are resulting in tighter credit as loan officers are less willing to lend. On the demand side, borrowers are less inclined to borrow. Both are bad omens.

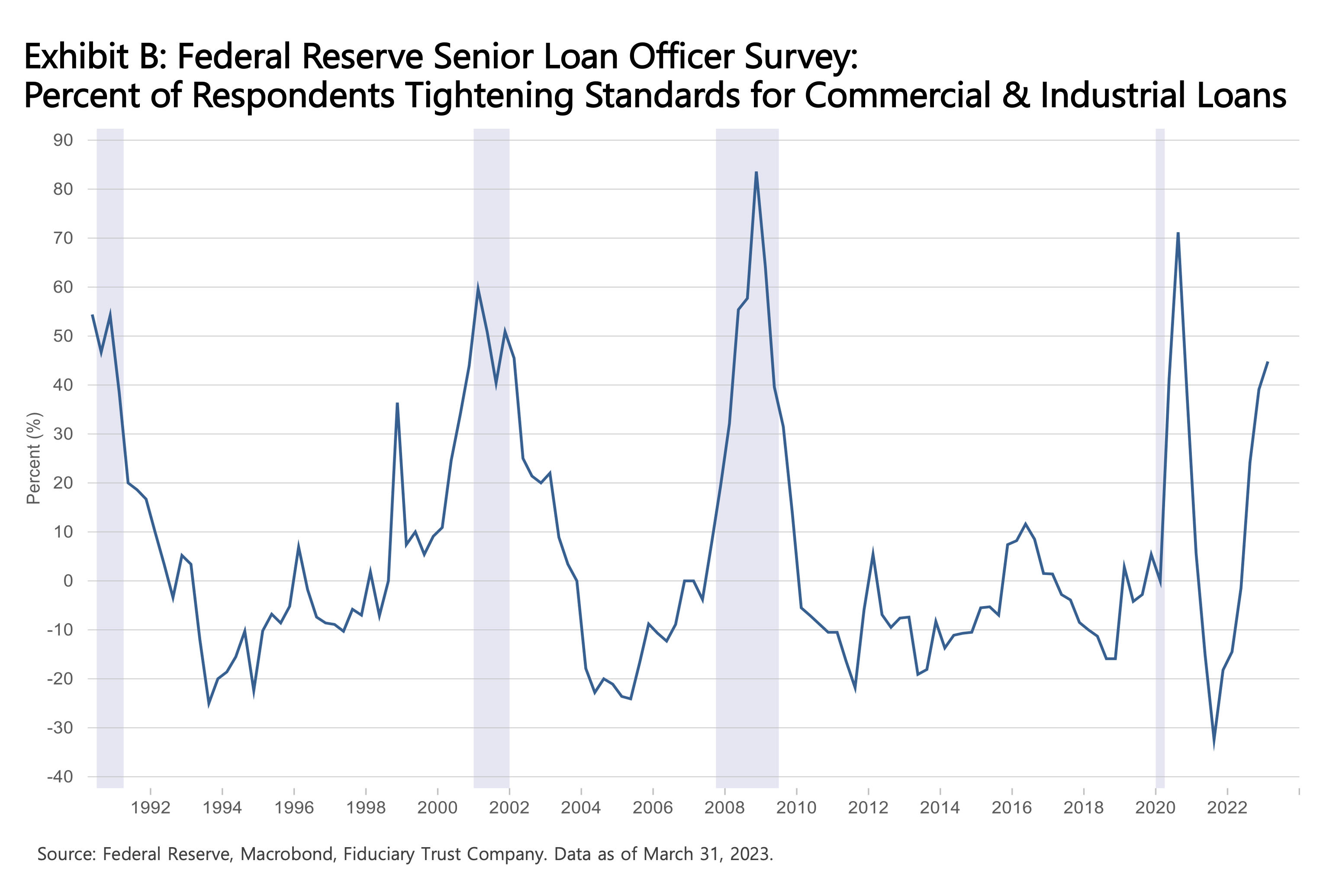

On the consumer side, early signs of stress are emerging. Credit card delinquencies are broadly turning higher, particularly so in small- to medium-size banks, according to Federal Reserve data (Exhibit C). Auto loan delinquencies are also on the rise. Overall, delinquencies are not at levels associated with recession, but the direction merits attention as it is a potential economic signal.

The one enduring bright spot has been the resiliency of the labor market. Month after month, the government has reported that hundreds of thousands of workers are finding jobs. Recessions fail to form when employment is rising. Worryingly, a closer inspection of employment trends reveals gathering threats. When businesses turn cautious, managers cut overtime rather than workers. It is a way to protect a labor force from the quarter-to-quarter swings in demand. If faltering business conditions persist, management is eventually forced to move from cutting hours to cutting people. Employment falls and the unemployment rate rises. Monthly data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics reveals a rolling over in overtime hours in the manufacturing sector. As predicted, employment growth is falling. Thankfully, it has not turned negative, but the headlines announcing job cuts and reduced hiring expectations seem to be growing.

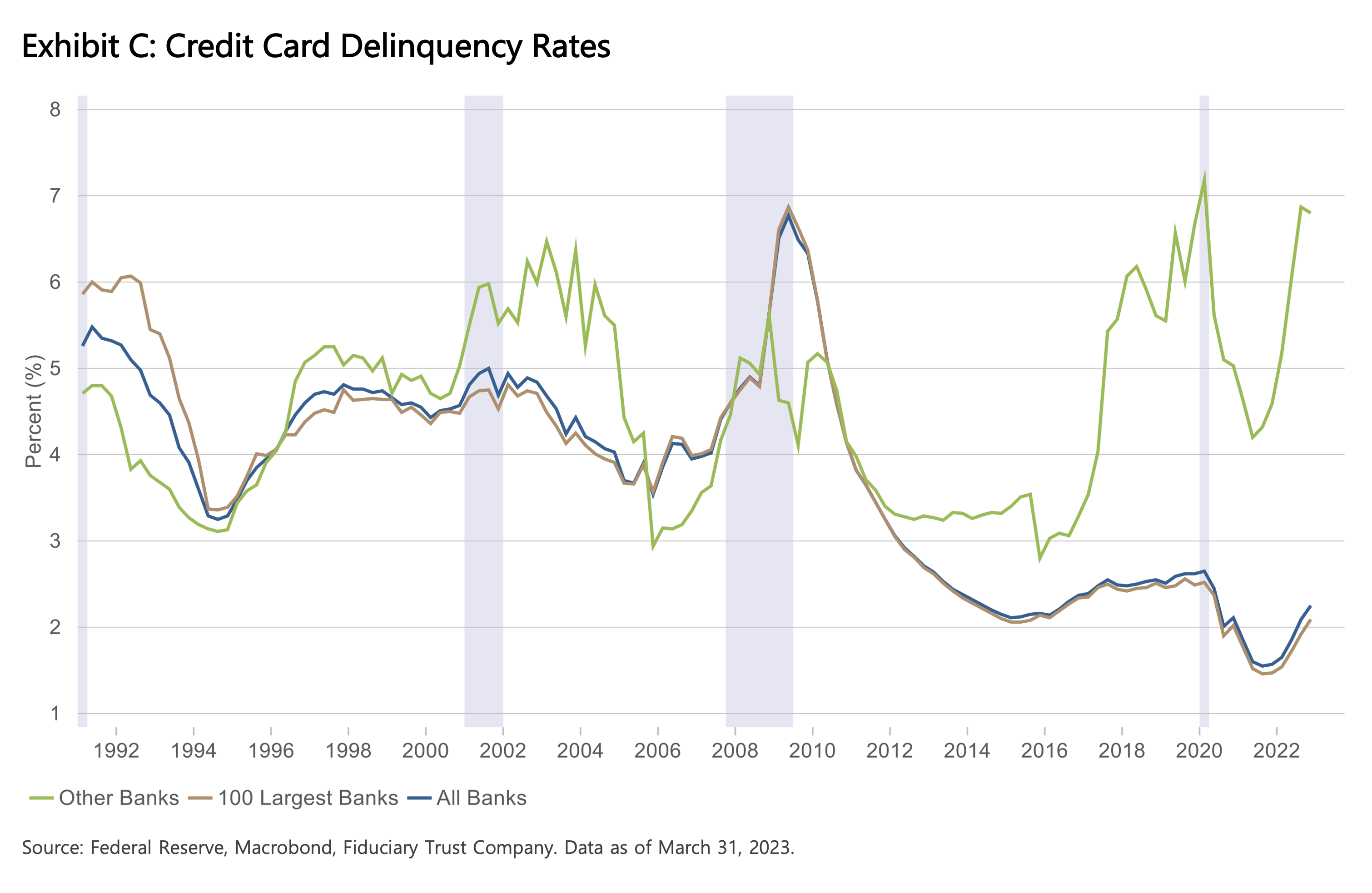

Markets are a forward discounting mechanism and an aggregation of recession forecasts compiled by Bloomberg places the odds of recession in the next year at 65%. Last summer the odds were at roughly 30%.2

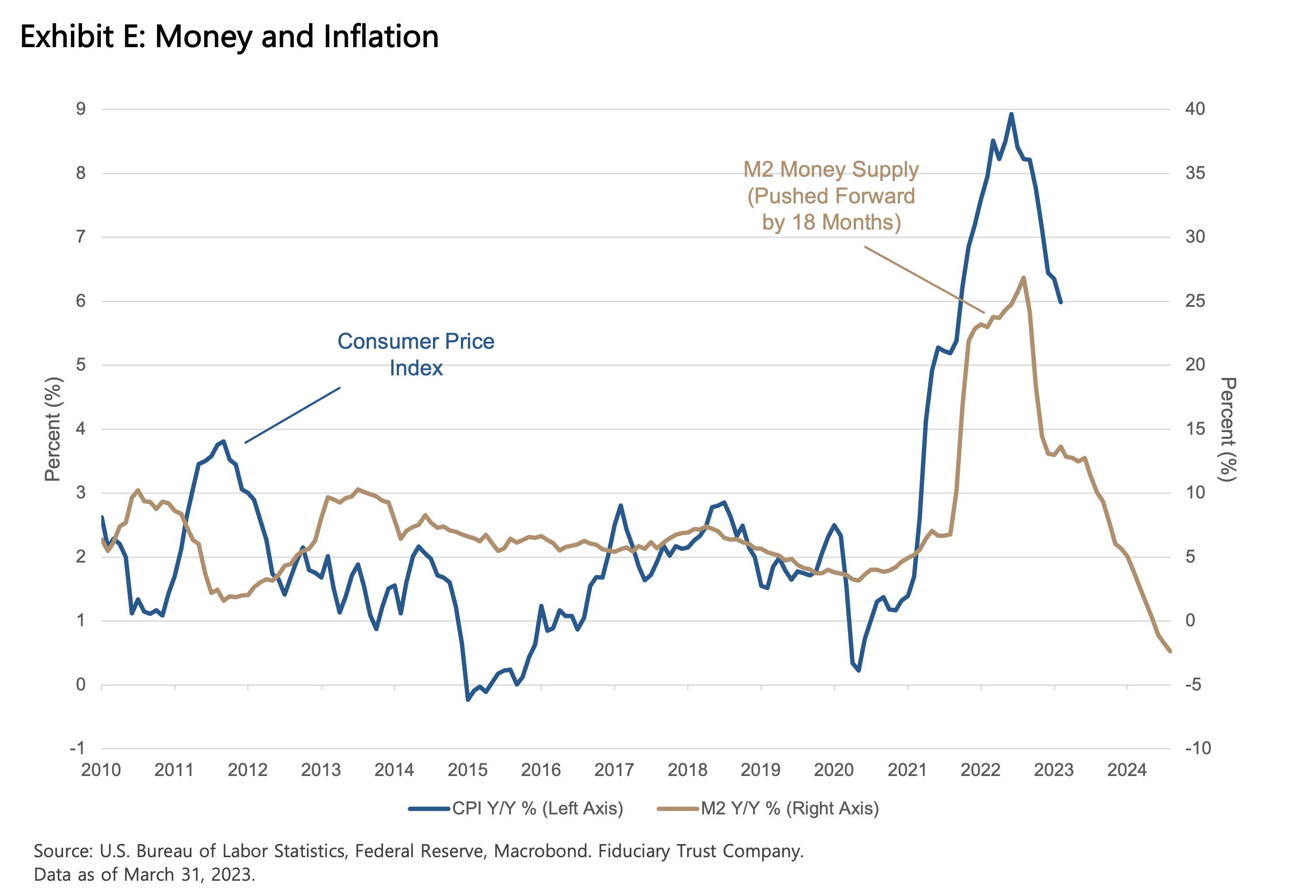

A recurring question we get is how long interest rates will remain elevated, which is really asking how long inflation will remain a problem. The answer can be found in the relationship between the growth in the money supply and the inflation rate.3 As Exhibit E reveals, the inflation rate (the price of things) follows the path of the money supply with a lag of roughly 18 months. M2, which is a broad measure of money in the economy, has been on a consistent decline since last June, suggesting another ten months of elevated but receding inflation.

The big question of where inflation settles remains unresolved. Does it return to the 1% to 2% band of the last decade, or does it settle into a higher level as the impact of a structural change in the labor market, de-globalization, and war establish durably higher inflation in the 3% to 4% range? If it is the latter, then a new financial age is set to commence, as the price of money can no longer be near zero.

Markets Perspective

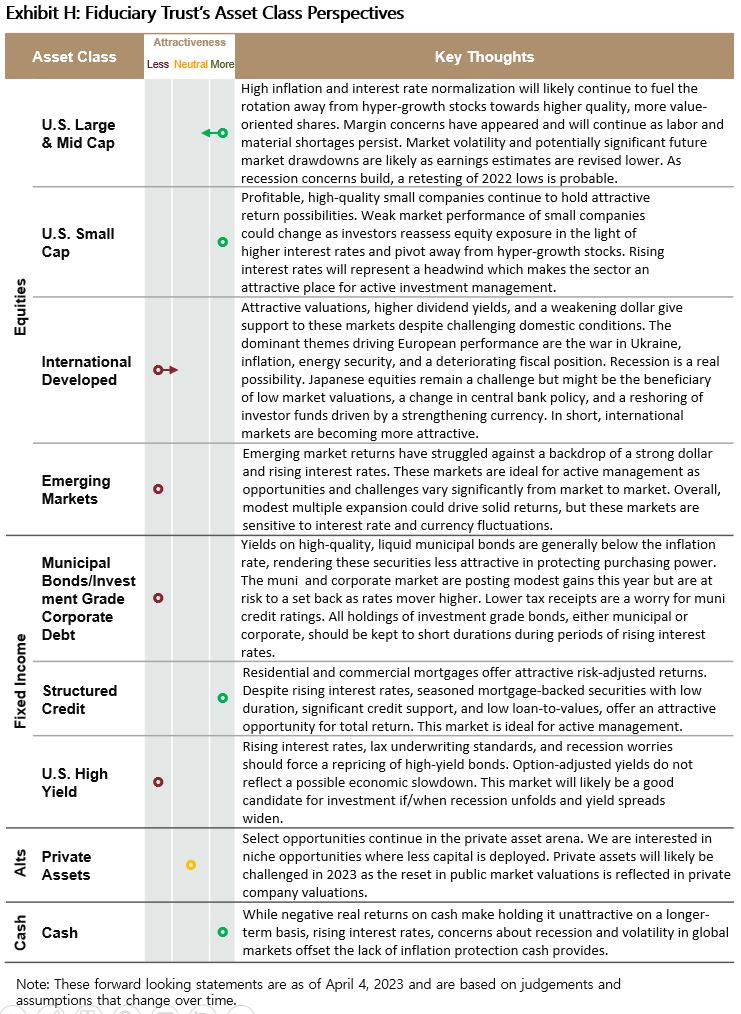

Equity and high-yield bond valuations are not signaling trouble ahead. The price/earnings multiple on the S&P 500 Index remains a healthy 18 times recession-free earnings. If we factor in a modest 10% decline from consensus profit estimates of $220/share, earnings drop to $200/share. This pushes the multiple to 20 times earnings, a princely sum in the face of high inflation and rising interest rates. This suggests stock prices should decline as investors rerate equity valuations.

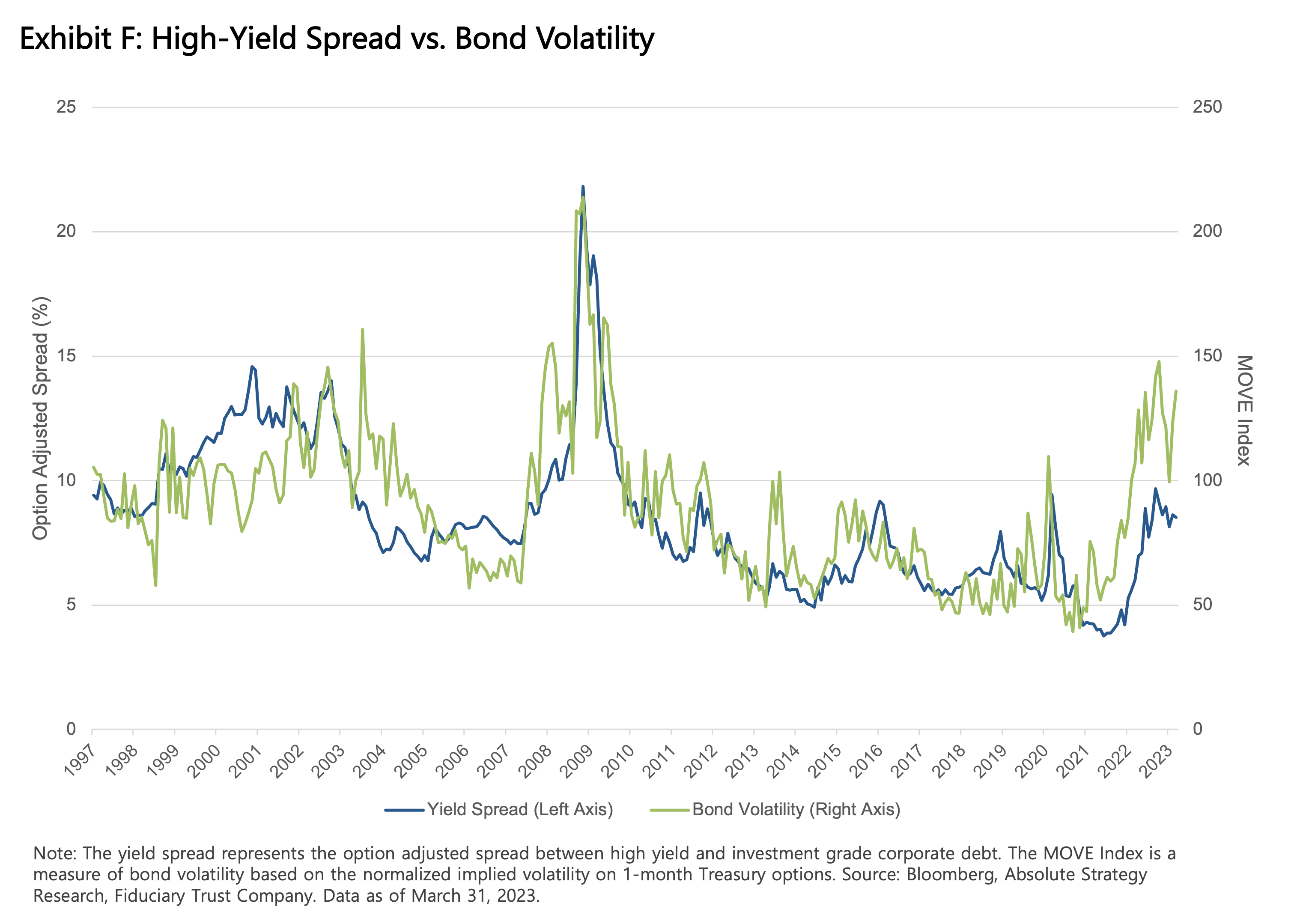

The financial cousin of equities is high-yield bonds, which tend to move in concert with stock prices. Yield spreads on high-yield bonds, while rising, are not at levels that clang danger. We do note, though, the break in Treasury market volatility and the yield spread between high-yield and investment-grade bonds. The relationship appears to be out of kilter, suggesting the dislocations roiling the Treasury market have yet to impact high-yield bonds (Exhibit F). Yield spreads between 6% and 8% represent a zone of opportunity for profitable investment.

In our last market letter, we highlighted the increased attractiveness of developed international markets. These markets have performed exceptionally well against a challenging backdrop. Euro Stoxx Index and Nikkei index advanced 10.8% and 5.5%, respectively, compared to the S&P 500’s 4.8% gain this year.4

As price pressures continue to bedevil profit margins, and tight money policy exacerbates bankers’ skittishness, markets are likely to retest the lows of 2022. Investor faith in a return to easy money and profits will collide with the reality that the state of play has fundamentally changed.

Looking back on events in March, one cannot help but sense that something has shifted and that something will set the course of events over the coming quarters. The echoes of Shakespeare are faint but audible: those damnable Ides of March.

1 KBW Bank Index max-min price movement from March 2 to March 24, 2023. Data via Bloomberg.

2 United States Recession Probability Forecast via Bloomberg, March 29, 2023

3 The money supply measures money in different forms: cash, money market funds, checking accounts, etc.

4 Dollar-based returns via Bloomberg.

Disclosure related to Bloomberg indices: Bloomberg Index Services Limited. BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Indices. Bloomberg does not approve or endorse this material or guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, nor does Bloomberg make any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom, and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, Bloomberg shall not have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.