Improving the world through charitable giving is an important priority for many individuals. More than a third of high-net-worth individuals entering their 50s cited helping others as a primary concern regarding their wealth.1 Because maximizing the impact of philanthropic giving is typically a top priority, donors should understand the various structures that are available for implementing their charitable gifts to determine which option best meets their personal objectives.

When choosing a charitable giving vehicle, some key factors a donor should consider are:

- Charitable tax deduction level

- Ongoing control

- Flexibility

- Setup and operating costs (both monetary and time-based)

- Income stream to donor or others

- Other features: anonymity, engagement of family members

The relative importance of these characteristics to the donor will enable the donor to determine which giving approach is the best fit for his or her philanthropic goals.

The approaches and vehicles used for charitable giving can be divided into three broad categories:

Direct:

- Description: The donor makes gifts of cash, securities, or other assets directly to a charity.

- Giving approach: Direct Gifting

Conduit:

- Description: The donor makes a gift to a charitable giving entity; over time, the entity distributes the assets to one or more charities.

- Giving approaches: Donor-Advised Funds, Private Foundations

Split-interest:

- Description: The donor makes a gift of assets; the donor or the donor’s beneficiaries receive an income stream, and then one or more charities receive a remainder amount (or vice versa).

- Giving Approaches: Charitable Gift Annuities, Charitable Remainder Trusts, Charitable Lead Trusts

Direct Gifts

The most straightforward way to give is by making a direct contribution of cash or other assets—including appreciated securities—to a charity. The clear benefit of a direct gift lies in its simplicity. Direct gifts are also tax-efficient because the donor is generally eligible for an income tax charitable deduction and will not recognize embedded capital gains on appreciated assets.

One popular variation of direct gifting is a qualified charitable distribution (QCD) made from the donor’s individual retirement account (IRA). While IRAs were not created for charitable gifting purposes, individuals over 70½ may donate up to $100,000 per year (indexed for inflation beginning in 2024) from their IRAs directly to IRS-qualified public charities. No income tax charitable deduction is available for this gift, but the distribution does count towards the donor’s required minimum distribution (RMD) for the year, if applicable, and is not included in the donor’s income. Recent legislation (the SECURE Act) has increased the beginning age for taking annual RMDs from an IRA, but age 70½ remains the eligibility age for QCDs.2

QCDs must be made from an IRA, not from a qualified retirement plan such as a 401k or 403b, and must be directed to public charities, not to private non-operating foundations, supporting organizations or donor-advised funds. However, a donor-advised fund can be a beneficiary of an IRA, payable at the IRA holder’s death.

Conduit Gifts

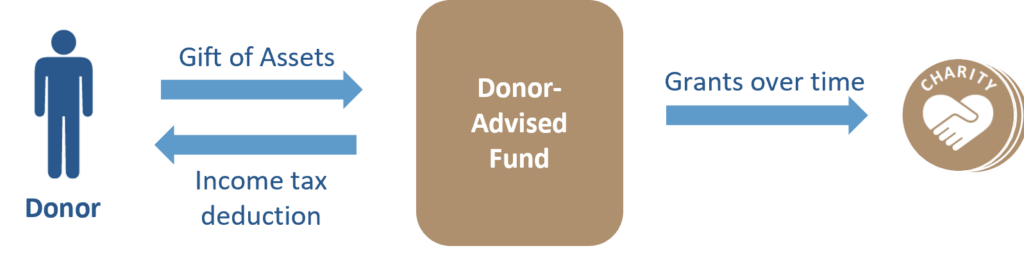

Donor-Advised Funds

For donors seeking a cost-effective and tax-efficient way to benefit charities, a donor-advised fund (DAF) provides an option that has become distinguished for its flexibility and convenience. Reflecting its attractiveness, grants from DAFs in recent years have expanded at seven times the rate of the expansion of total charitable giving.3

A DAF is a separately identified fund comprised of donor contributions maintained and operated by a sponsoring organization that is a 501(c)(3) public charity (such as Fiduciary Trust Charitable). The sponsoring organization has legal control over the donated assets, but the donor or other designated parties retain advisory privileges to the fund. Such advisors make recommendations regarding the distribution of the funds and may have a voice regarding the investment of assets in the account.

A primary advantage of gifting to a DAF is the immediacy of the tax deduction combined with the flexibility of recommending charitable grants over time. Given that DAF-sponsoring organizations are public charities, contributions to DAFs are eligible for maximum charitable tax deductions. The types of assets that can be contributed to DAFs range from cash and publicly traded securities to restricted stock, real estate, tangible personal property, and other illiquid assets, depending on the sponsoring organization’s guidelines. Any growth of the assets inside the DAF generally will be tax-free, increasing the amount available for distribution to charity. DAFs are appropriate for donors with smaller balances to devote to charitable causes, but can also be attractive for large gifts. In fact, there are individual DAFs holding well in excess of $100 million in assets.

Learn More: “Minimizing Taxes with Charitable Deduction Bunching“

Some restrictions do apply to DAF distributions, however. For example, under IRS rules, DAFs may not distribute to individuals or provide a “more than incidental benefit” to the donor. Most DAF-sponsoring organizations require that any grantee organization be a 501(c)(3) organization classified as a public charity and, therefore, do not permit grants to private foundations. Currently, there are no IRS-imposed requirements for the timing and amount of DAF distributions. DAF-sponsoring organizations, however, may have their own distribution rules, such as requiring at least one distribution every two years, or a minimum distribution amount per grant.

DAFs can provide a simple way to involve multiple generations in philanthropy. Younger children can be included in discussions regarding grant recommendations and adult children can be named as advisors or successor advisors to the fund. Because DAFs are generally not tied to specific grantee charities, as a family’s philanthropic vision changes and matures, the family can revise its grant recommendations accordingly. DAFs can also be used to make anonymous donations to charities, which can be beneficial to both family and individual donors.

Learn More: Fiduciary Trust’s Donor-Advised Funds Program

Private Foundations

While DAFs are among the fastest-growing charitable giving vehicles, private foundations remain one of the most popular structures, particularly for high-net-worth individuals seeking to exert influence in a particular cause or to create a philanthropic family legacy. Giving via foundations accounts for nearly 20% of all charitable contributions, and represents the largest source of charitable dollars outside of direct gifts from individuals.4

Private foundations are separate legal entities, formed as trusts or corporations, which receive their funding from a single donor or a small number of donors instead of from the general public. A primary appeal of creating a foundation is the level of control the founder can maintain over the entity. The founder can ensure that his or her specific vision is built into the foundation’s organizational structure and can retain decision-making authority over the foundation’s activities, including investments and grants. The donor can serve as trustee, for example, or can designate the members of the foundation’s governing body.

Donors also like the flexibility of foundations. Foundations can operate as grant-making entities or can engage in their own charitable activities. These giving programs and activities can be modified over time to reflect the evolving charitable interests of the founder and the founder’s family. Foundations also can engage in mission or impact investing and program-related investments. Private foundations are a useful vehicle for family philanthropy. Foundations can continue for many generations and younger family members can be trained in philanthropy and investment management by serving in roles in the foundation’s operations.

Gifting to a private foundation is not as tax-efficient as gifting to a DAF or another public charity. Contributions of cash to a private foundation are subject to an income tax charitable deduction limitation of 30% of adjusted gross income (AGI), and gifts of securities held for more than one year or other capital gain assets are subject to a limitation of 20% of AGI. Such gifts to DAFs, on the other hand, are subject to limits of 60% (reverting to 50% on January 1, 2026) and 30% of AGI, respectively.5 In addition, appreciated, non-publicly traded assets held for over one year that are donated to a DAF will receive a deduction based on the assets’ fair market value, but the deduction allowed for such assets donated to a private foundation will be limited to the donor’s basis.

Private foundations are fairly complex gifting vehicles requiring donors to seek assistance from attorneys, accountants, and other professionals at both the set-up stage and during operation. Foundations are subject to special oversight rules, including a general requirement to pay out at least 5% of assets each year for charitable grants or activities, a net investment tax of 1.39%, strict prohibitions on self-dealing, restrictions on owning operating businesses or “risky” investments, and restrictions on making grants to individuals and non-public charities. The cost of operating a foundation can be high in terms of direct expenses, particularly if the foundation employs staff, and also the governance and administrative time required of its trustees. While foundations can be created with modest funding, given the costs involved and minimum distribution requirements, these vehicles are generally more appropriate for families with at least $1 million or more to commit to the entity.

Learn More: Fiduciary Trust’s Services for Foundations

Split-Interest Gifts

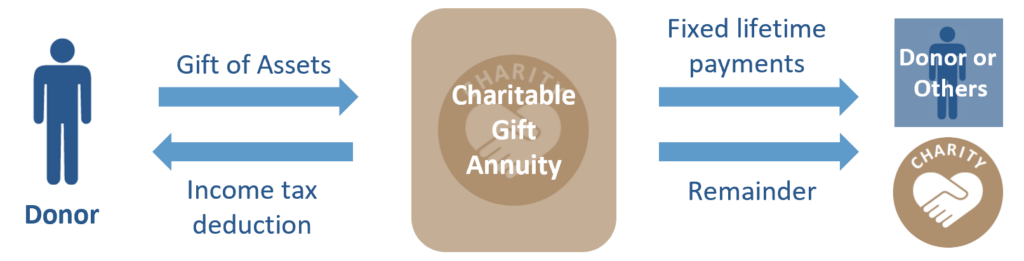

Charitable Gift Annuities

A charitable gift annuity enables a donor to make a gift to a nonprofit organization while creating an income stream to the donor or other individuals over the individual’s lifetime. These vehicles are created through a contract in which a charity agrees to pay the donor or another beneficiary an annual sum of money for life in exchange for a donation of cash or other assets. The amount of these annuity payments is generally based on an anticipated 50/50 split of funds between the donor and the charity, and so will depend on the gift annuity rate currently used by the charity, the age of the person receiving the annuity, and the amount of the original gift. This annuity amount becomes a fixed obligation of the charity. Thus, neither later market conditions nor investment returns will change the payment amount. Generally, for this type of gift, the amount eligible for the donor’s income tax charitable deduction is the difference between the fair market value of the assets donated and the value of the annuity contract.

While charitable gift annuities are more complicated than direct gifts, they are still fairly simple to establish, and they also include the benefit of a steady stream of income for the beneficiary. When the beneficiary receives each annuity payment from the charity, part of the payment will be taxable to the beneficiary as ordinary income, and part will be exempt, in accordance with certain IRS-published interest rates. Using appreciated property for a charitable gift annuity can increase the gift’s effectiveness by minimizing and spreading out the capital gain for income tax purposes.

The donor can be the recipient of the income stream of the annuity, or the donor can name another individual as the annuitant, including a spouse, parent, or other family (or non-family) member. Selecting an annuitant other than the donor or the donor’s spouse, however, will have gift tax implications. Charitable gift annuities can be established to last for the lives of either one or two individuals, but they are not available for a term of years. Thus, there is no compensation to the donor or the donor’s family for the early death of the annuity recipient. Upon the death of the annuitant (or upon the death of the surviving annuitant if there are two), the charity’s obligation to make annuity payments ends.

Recent legislation (SECURE Act 2.0) allows for IRA owners ages 70 ½ and older to fund a special type of charitable gift annuity using exclusively a QCD from an IRA. This can be done only once during the donor’s lifetime and is limited to $50,000 per individual (for 2023; adjusted annually thereafter for inflation). However, spouses can combine their funding into a single annuity vehicle. The annuity payments can benefit only the donor or the donor and the donor’s spouse and are taxable at ordinary income tax rates. As with regular QCDs, the donor does not receive a charitable deduction for the amount contributed, but does exclude the QCD amount from the donor’s income, and can also count the QCD towards any IRA-required minimum distributions.

Charitable gift annuities can be a good choice for donors who wish to make a significant gift, and who also would like the security of regular, fixed income payments as a component of retirement planning. This guaranteed income can be particularly attractive in times of market volatility. Because the income payment of a charitable gift annuity is the charity’s obligation under the annuity contract, the donor will need to assess the charity’s financial stability. Not all charities are large enough or sophisticated enough to be able to enter into a charitable gift annuity, so donors may have more limited options for choosing recipient charities than with direct gifting or conduit gifting strategies. In addition, a charitable gift annuity will benefit only one chosen charity. On the spectrum of charitable giving vehicles, gift annuities are generally less complex to establish and administer than other options, and in many cases can be established for contributions as little as $5,000.

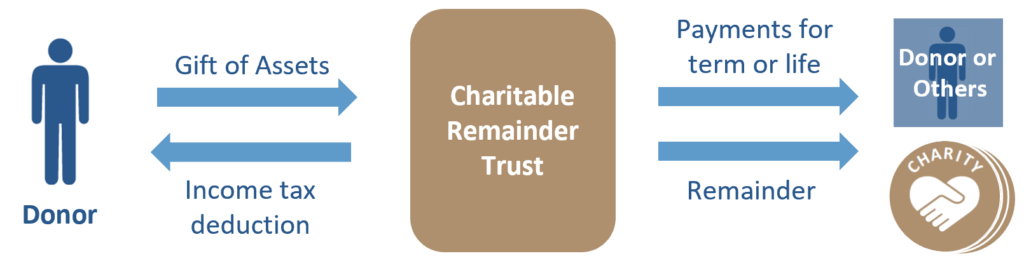

Charitable Remainder Trusts

Charitable remainder trusts (CRTs) are similar to gift annuities in that they provide a recurring income stream to the individual making the contribution or to other chosen beneficiaries, with a remainder to charity. A CRT, however, is not a contract between the donor and a charity; it is an irrevocable trust established entirely by the donor. While a CRT is generally more complex to establish than a charitable gift annuity and requires the involvement of an estate planning attorney, it also provides the donor with more control and more flexibility. There are two types of CRTs: charitable remainder annuity trusts (CRATs), which distribute a fixed annuity amount each year during the payment term, and charitable remainder unitrusts (CRUTs), which distribute a fixed percentage of the trust assets, revalued annually, during the payment term.

A donor’s flexibility when establishing the terms of a CRT is restricted by IRS-proscribed limits. The donor may name himself or herself as the income recipient and may include a spouse as a concurrent or successor income recipient. The donor may also name non-spouse family members or others who are living at the time the trust is created, but doing so will create gift tax considerations. The donor may choose the payment term, which may be for the lifetime or lifetimes of one or more beneficiaries, or for a term of years not to exceed 20 years. The annuity amount (for CRATs) and the unitrust amount (for CRUTs) may also be selected by the donor but must be within 5% and 50% of the value of the trust assets, valued at the date the trust is created for CRATs and valued annually for CRUTs. The trust term and annuity amount must also be set so that the value of the CRAT or CRUT remainder interest is projected to be high enough and not likely to be exhausted before the charity receives it. The IRS interest rate, the ages of the trust beneficiaries, and the length of the payment term will affect these calculations.

CRTs enable the donor to have a certain level of control. So long as the CRT is drafted with appropriate terms, the donor may serve as the CRT’s trustee and thus continue to control the trust’s investment of its assets. In addition, the donor may retain the ability to remove trustees and name successor trustees. CRTs also provide the donor with flexibility. The donor can identify more than one charity to receive the remainder and can name both public charities and private foundations. The CRT can also be drafted so the trustees have the power to name or change the charitable beneficiary during the term of the trust.

When a donor transfers assets to a CRT, the donor is eligible for a current income tax deduction on a portion of the gift, even though no assets will be going to a charity at that time. The deduction will be based on the term of the trust, the projected income payments, and certain IRS interest rates reflecting the assumed rate of growth of trust assets. Donors can only make one contribution to a CRAT (when the CRAT is established), but donors are permitted to make multiple contributions to CRUTs.

As with other charitable gifting vehicles, the use of appreciated assets increases the tax efficiency of the donor’s gift. The CRT is particularly attractive for diversifying a concentrated investment position as there is no tax due at the time of the asset sale. Thus, the value of the income stream to the non-charitable beneficiaries and the amount remaining for charity will be higher than if the donor sold appreciated assets, paid tax on the gain, and then contributed the remaining cash. One advantage of a CRT is that the trustee, not the charitable beneficiary, will control the timing of the sale of contributed assets and the ongoing investment of trust assets.

The same recent legislation that allows individuals to make one-time QCDs from IRAs to fund charitable gift annuities, as described above, also provides that CRTs can be the recipient of the one-time QCD. However, given the modest $50,000 lifetime limit and the requirement that such life income charitable vehicles be funded exclusively with the QCD, the technique is more likely to be used for funding a charitable gift annuity than a CRT.

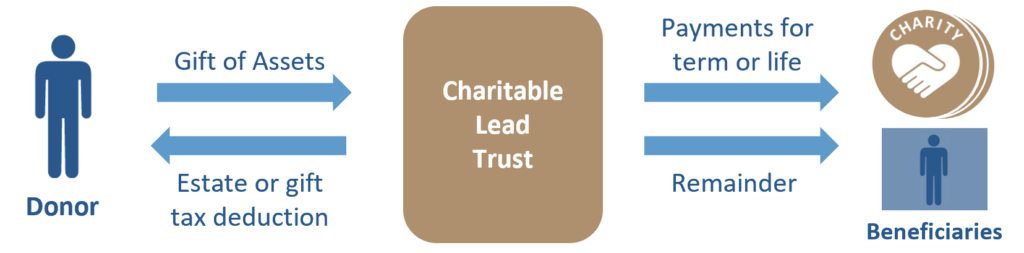

Charitable Lead Trusts

Similar to CRTs is the somewhat less popular charitable lead trust (CLT). A CLT is essentially the reverse of a CRT. For a CLT, the donor establishes a trust where income is paid first to a charity for a term of years or for an individual’s lifetime and then upon the expiration of that term, the remainder passes outright or in trust to the donor’s named beneficiaries. Unlike CRTs, CLTs have no limit on the number of years for the charitable term, and there is no minimum or maximum to the annuity or unitrust payment amount.

CLTs also differ in their taxation. The donor is not entitled to an income tax deduction upon creation of the CLT (unless it is structured as a grantor trust), but is entitled to an estate or gift tax charitable deduction for the value of the charitable lead interest. The CLT is a taxable entity that will receive charitable deductions for the amounts it pays to charity.

Learn More: Fiduciary’s Trust Services

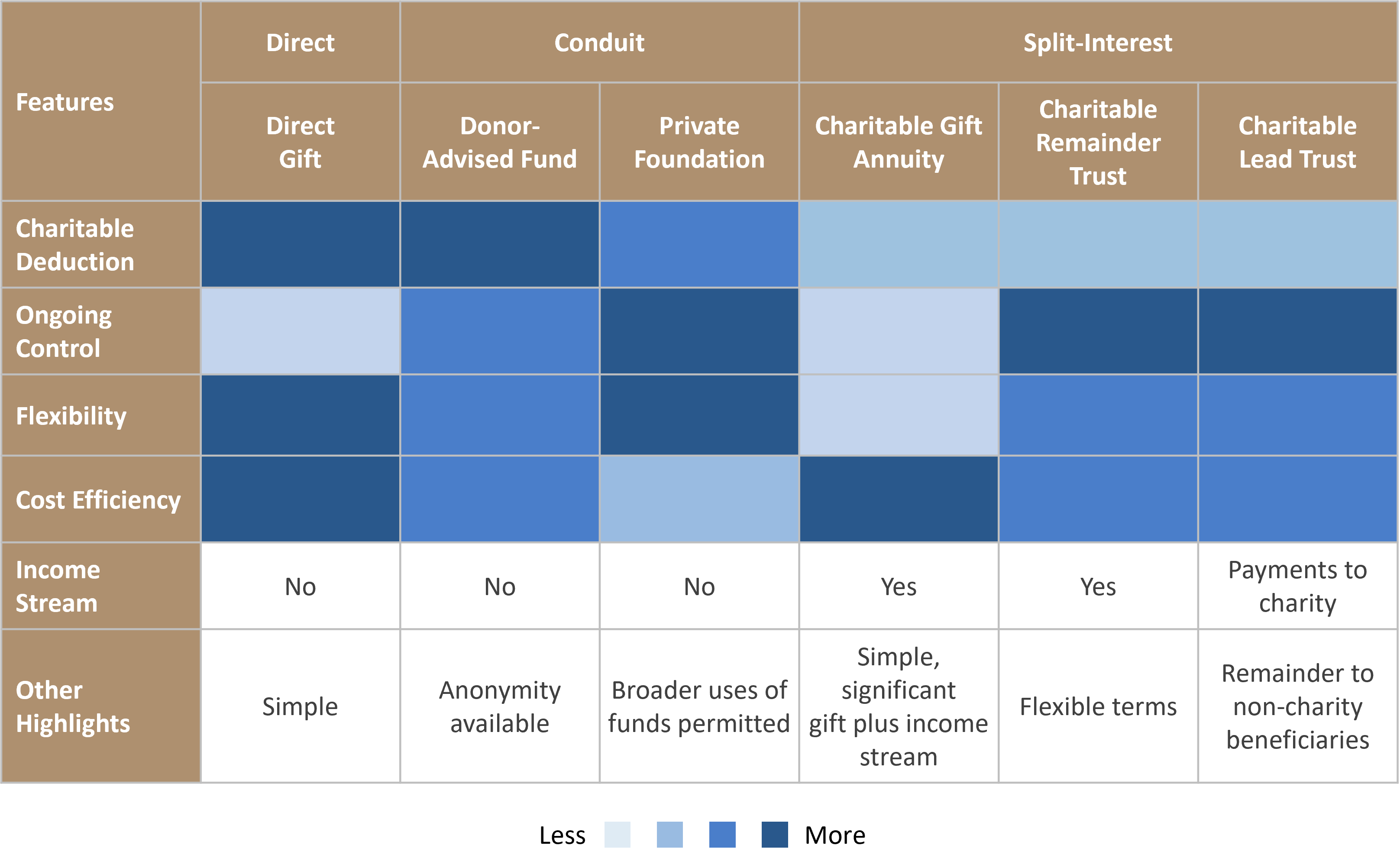

Comparison of Charitable Giving Approaches

Applying a Strategic Approach

When it comes to optimizing individual or family philanthropy, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Sophisticated donors need to assess the various aspects of direct gifts, conduit gifts, and split-interest gifts that are important to them to determine which approach will best meet their goals. It may be best for a donor to combine several gifting structures in order to achieve these goals and to increase charitable impact. For example, a donor may designate a donor-advised fund as the remainder beneficiary of a charitable remainder trust. A donor may also use distributions to a DAF to help the donor’s private foundation meet the foundation’s 5% minimum distribution requirement. An individual may wish to use an approach that results in gifts exceeding the standard deduction in any one tax year to be able to itemize the gifts and utilize the income tax charitable deduction.

Learn More: “A Perfect Pair: Private Foundations and Donor-Advised Funds”

Given the nuance and technical considerations that accompany these giving strategies and their role within a comprehensive wealth management and estate plan, individuals and families should consult their financial and tax advisors to understand which alternatives are most appropriate for their particular situations.

A video version of this material is available here.