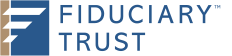

For decades, the national debt has been one of those perennial issues that comes and goes from the national spotlight, especially around election years. Yet heading into this election year, something feels different. The U.S. national debt now exceeds a record $34 trillion.1 And since the global pandemic, debt as a percentage of gross domestic product has hovered above 120% for the first time ever (it currently stands at 124%), surpassing borrowing in the aftermath of World War II, when total debt to GDP hit 119% in 1946.2

Exhibit A: U.S. Federal Government Debt Relative to GDP

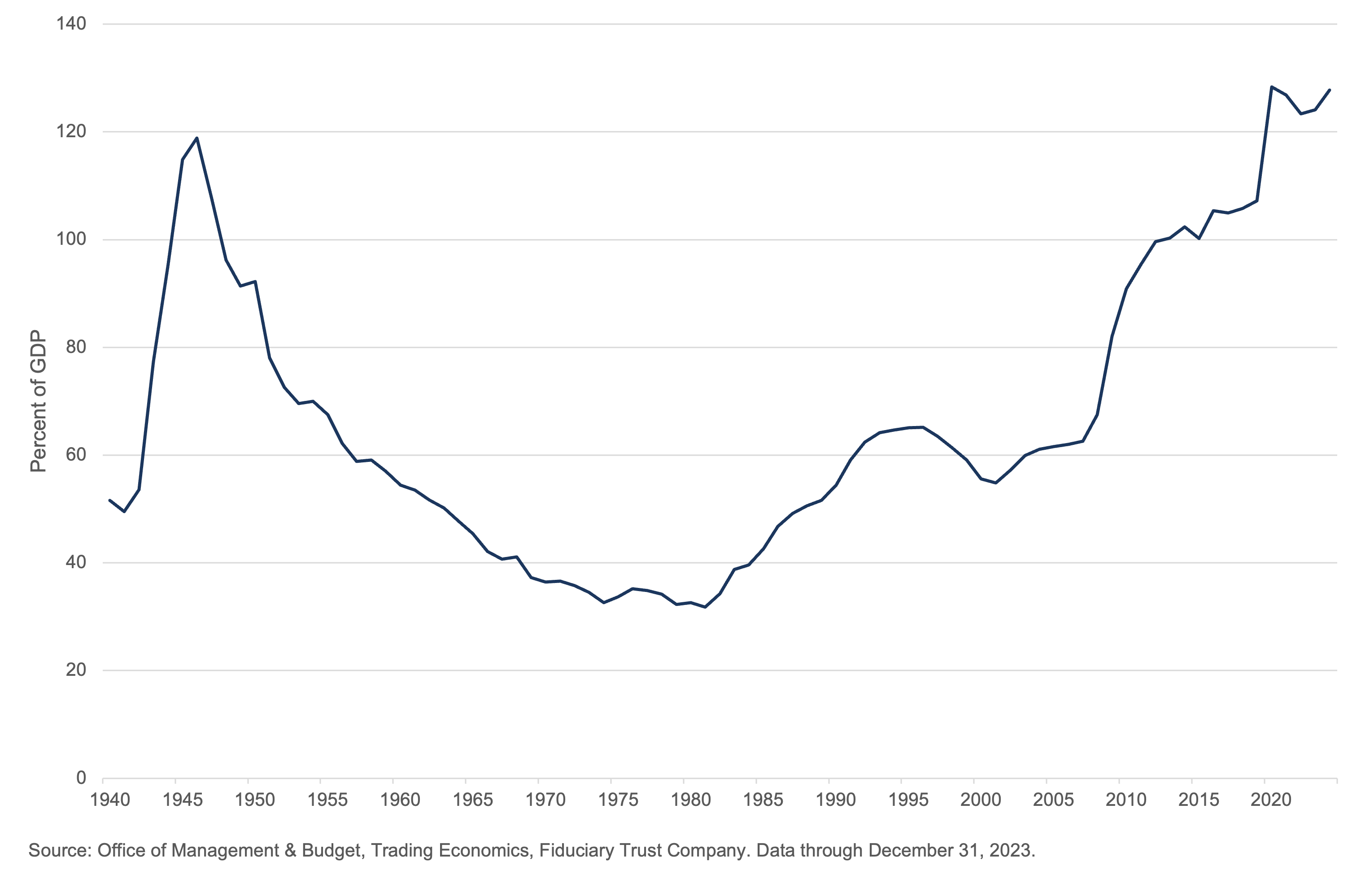

Exhibit B: U.S. Federal Budget Breakdown

Of course, debt is not a new problem for the federal government. The nation has owed money since its inception — $75 million was borrowed from the French government and domestic investors during the American Revolutionary War.5 Yet in the past five years, the size of the national debt has grown by $10.5 trillion, thanks to increased spending by administrations from both parties. The Trump Administration spent on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and then to counter the effects of the global pandemic and the Biden Administration spent on the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and aid to Ukraine and Israel toward their war efforts.

The question is, how concerned should investors be? To answer that, we must explore how the national debt impacts the economy, the financial markets, and investors.

How the Debt Affects the Economy

The national debt isn’t an abstract concept — it affects the economy in very real ways. For example, it reduces the government’s ability to make large investments to promote growth, as increased spending on interest crowds out spending in other areas. The government becomes forced to focus its spending only on necessities to keep costs down, leaving far less room for investments in education, R&D, and infrastructure improvements.

It also reduces investments made by the private sector, as debt leads to higher rates across the fixed income market, adding to borrowing costs of small businesses and large. Market rates are driven by several factors, including economic growth, the Federal Reserve’s policy reactions to that growth, and inflation. However, rates are also influenced by supply and demand, and more issuance of Treasury securities to finance the debt is likely to push up rates to attract investors.

This is likely to drive up borrowing costs for private businesses, eating into their earnings, hampering their ability to invest, and threatening their financial health. Indeed, amid rising rates last year, corporate debt defaults rose significantly, although they are still at relatively low levels according to S&P Global Ratings, which is forecasting further credit deterioration this year.6

What This Means for Investors

While the national debt’s impact on the economy is clear, the steps investors need to take to reflect these concerns are less so. For example, rising debt doesn’t always translate into poor returns for the stock market. As mentioned above, the last time the national debt approached 120% of GDP was in the mid to late 1940s, the stock market went on to gain 19.5% annually throughout the 1950s. Back then, however, the U.S. economy was still burgeoning and was able to grow fast enough in the aftermath of World War II to begin chipping away at the debt. That type of growth is far less likely today.

Higher rates potentially lower future stock market expectations, by weighing on corporate earnings. They also make competing vehicles, including savings accounts and fixed income instruments, more attractive on a relative basis. At the very least, higher rates require investors to rein in their expectations for stock market returns.

There are no short-term solutions to a problem that’s been building for more than 40 years, across numerous administrations. Regardless of which party wins the White House and control of Congress in November, the debt will not disappear. This is a multi-decade problem that requires a multi-decade fix.

This is where having an advisor to help you establish a proper framework for understanding the potential implications of the debt come into sharper focus. If you would like to discuss the positioning of your strategy and how to establish the proper guardrails in this coming election market, please reach out to Sid Queler at squeler@fiduciary-trust.com.

1 “The U.S. National Debt Is Rising By $1 Trillion About Every 100 Days,” CNBC.com. March 1, 2024.

2 United States Gross Federal Debt to GDP, Trading Economics.

3 The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034, Congressional Budget Office. Feb. 2024.

4 Ibid.

6 “Corporate Debt Defaults Soared 80% in 2023 and Could Be High Again This Year, S&P Says,” CNBC.com. Jan. 16, 2024.